Home Donate New Search Gallery Reviews How-To Books Links Workshops About Contact

Lens Sharpness

© 2011 KenRockwell.com. All rights reserved.

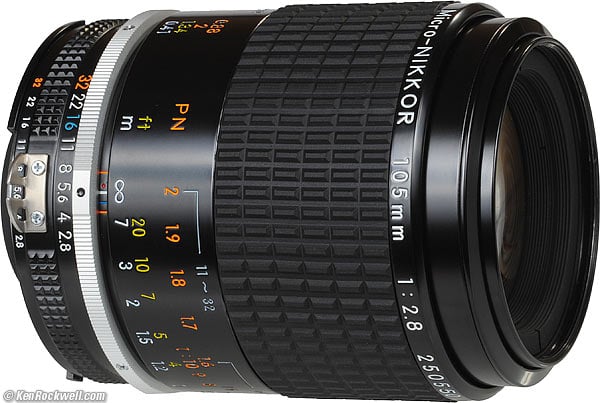

Nikon Micro-NIKKOR 105mm f/2.8 AI-s. This free website's biggest source of support is when you use these links to get your stuff from the same places I do when you get anything, regardless of the country in which you live. Thanks! Ken.

May 2008 Nikon Lenses Canon Lenses LEICA Lenses All Lenses

|

I use Adorama, Amazon, eBay, Ritz, Calumet, J&R and ScanCafe. I can't vouch for ads below.

|

Sharpness is the most overrated aspect of lens performance.

Lens sharpness seems like it ought to be related to making sharp photos, but it isn't.

Sales and marketing departments fuel this misconception because it scares people into buying new lenses. Sharpness is easy to test and analyze, so magazines oblige less experienced photographers with reams of colorful charts and graphs. People would make far better pictures if they spent time learning how to make great photos with what they already own instead of worrying about their tools.

Photographic lenses, used properly, have always been sharp, even at the dawn of photography in the 1840s. Optical design is a much older science than photography. The reasons some photos aren't sharp rarely have anything to do with the lens.

"Any good modern lens is corrected for maximum definition at the larger stops. Using a small stop only increases depth..." Ansel Adams, June 3, 1937, in a reply to Edward Weston's request for lens suggestions, page 244 of Ansel's autobiography. Ansel was telling him to stop worrying about lens sharpness, since all the ones he was considering were sharp. This was the 1930s. Today even crappy lenses, including plastic lenses on most disposable cameras, are sharp when used properly.

In 2008, sharpness is the last thing about which you need to worry when selecting a lens. Even the cheapest SLR and compact cameras lenses are sharper than expensive lenses used to be, and all are sharper than most digital camera's ability to resolve fine details.

I'm writing this page because I'm embarrassed at how I have to use a lens improperly just to show its limitations in a lens review. I know how to make almost any lens or product look bad by using it incorrectly and then enlarging the results for all to see. I'm embarrassed because this isn't the correct way to write a useful review, but it's the sort of thing that people who read reviews like to read.

Lens sharpness has little to do with anything. It gets too much coverage because it's easy to test and analyze.

If you want impressive interactive 3-D color graphics, all anyone has to do is buy some software, shoot a target or two, and the software generates tons of impressive charts and graphs based on whatever it's fed. That's the problem: the charts don't tell as much as an actual series of many images says to an experienced observer, and the charts only can show what little is seen with the few controlled images fed to the software.

Testing lens sharpness is less relevant today than it was in the 1950s! In the 1950s, a lens was just an optical tube with no communication to the camera body. Even the diaphragm had to be opened and closed manually for each photo! "Automatic" diaphragms that opened and closed for each shot didn't become common until the 1960s. This is why old manual lenses often say "Auto," because automatic diaphragms were a big deal in the 1960s. In the 1950s and before, testing a lens' optics in the sterility of a lab made as much sense as anything.

Today the optics are only a small part of any camera system, and the optics are so good that they render lab testing irrelevant unless you're a lens designer. We need to worry about how a lens works as part of a much larger system of live tracking autofocus, aperture and exposure control, distance information fed to the metering system, vibration reduction, zooming, and more.

Because most lenses won't work today unless they have a camera body for shore power and life support, testing the optics alone in a lab no longer means anything to photographers. Testing lenses with the cameras on which they are used means much more, which throws magazines into a tizzy since they no longer can run a lens through a solitary lab test and have anyone care.

Know Your Limits top

I need to know the limits of each part of my system so that I can work around them. If I know a lens is softer wide-open, then duh, I know how far to stop it down to get fantastic results. It's the great results I seek; finding the limits is merely a means to getting great results.

The first thing I've always done when I've bought a new camera or lens is to push it to its limits. I find the limits, make a note of it (which is what started this website), and then go out and shoot. I don't worry about it again.

Sadly, many people try to test their lenses, but get disappointed and think they have a defective product when all they've found is its limits, or more often, limitations in their own technique. Let me assure you, every product has its limits, and with digital cameras today, anyone can find them.

Only idiots find something's limits, and let themselves get stuck there complaining about it. It's every artist's duty to find his tools' limitations so he can work around them. Americans didn't walk on the moon in 1969 by sitting around complaining about all the reasons we couldn't get there.

Why Lens Sharpness Doesn't Matter Anyway top

Even with film, most people considered small 8x12" (20x30cm) prints as "enlargements." People often thought they were testing sharpness by looking at 4x6" (10x15cm) "jumbo" prints. This was always ridiculous, because even the crappiest 35mm camera can easily make sharp 8x12" prints. Even when I started with 35mm as a kid in the 1970s, I knew that you had to print at 20 x30" (50x75cm) in order to see any lens limitations. It was easy for me to see things on my transparencies under my microscope or with my slide projector that simply didn't make it to 8x12" prints.

Most gear has always been much better than people's abilities to use it. Making big prints usually lost more sharpness from sloppy enlarging technique than any limitation of the taking lens. Most people still have no idea of just how good even the simplest of equipment is today.

In the old days, we went blind staring at film with loupes (usually 8x ~ 22x) and microscopes (30x and up). Today, anyone can look at digital images at 100% on their computer or camera's LCD, which is at least 30x magnification from even the lowest resolution DSLR. Likewise, anyone can share all these greatly magnified images across the Internet. (30x means how much larger the on-screen image is compared to the original image formed by the lens.)

The afternoon I got my first Canon 16-35mm f/2.8 L II, it looked pretty nasty shooting brick walls. I got over it, and headed out the next morning to shoot it in Yosemite, and got some of my best shots ever. Why? Simple: walls have nothing to do with real subjects, and no one shoots at f/2.8 in decent light. Stop down and the lens is marvelous, even in the corners at 16mm. In dim light, where you might use f/2.8, corner sharpness doesn't matter because the subject is usually dark there!

When I spoke with the folks at Canon in person, we all had a good laugh at how Canon had to re-do an already excellent lens just so people who weren't using it properly would be happy. No one complained in film days when only pros owned Canon's exotic 16-35mm f/2.8. Of course Canon is more than happy to offer a newer and more expensive lens, but we still scratch our heads as to why some people, other than lens designers, worry so much about this.

In real-world photography, natural factors do more to screw up a picture than any lack of lens sharpness. Sharpness tests are unlike real photos because a test does everything possible to eliminate any source of unsharpness. In a lab, nothing moves and the target is usually flat. Only corn dogs use cameras to photograph flat test charts; smarter people stick flat charts in a $50 scanner for better results!

In reality, everything moves, and nothing is flat. If nothing is flat, then only one point is in perfect focus while the rest isn't.

Therefore, there may be no real plane of perfect focus, because most lenses have saggital and meridional (imaginary) planes of perfect focus which diverge. Planes of perfect focus are usually different for different colors, all this gobbledygook meaning that there is no single real plane of perfect focus anyway.

Most lens makers' sharpest lenses are their 300mm f/2.8, 400mm f/2.8, 500mm f/4 and 600mm f/4 ED and L series lenses. Look at their MTF graphs, and they really do have virtually perfect performance. Unfortunately, long lenses have even more stacked between them and a sharp picture. Not only do long lenses have paper-thin depths of field, but their biggest barrier to sharpness is our atmosphere! Even at reasonable distances, heat shimmer is so magnified by long tele lenses that it's often a big barrier to sharpness. Fog and haze at long distances doesn't help, either. Long teles are subject to the same things that vex astronomers, which are called "seeing conditions."

A sharp photo needs good lighting, clear air, getting the subjects to sit in the plane of best focus, and an imaginative photographer. Depth-of-field, imperfect focus and subject and camera motion are the major reasons photos are rarely as sharp as they could be. Lens imperfections almost never matter in real photography.

Who Cares? top

Artists and good photographers avoid putting sharp, contrasty and important image elements along the edges of an image because these details draw our eyes out of the image. Photographers especially avoid putting anything in the far corners. An effective image keeps viewers' eyes glued to the subject and inside the picture. Details at the periphery pull eyes away from the subject which weakens images.

When lenses get softer in the corners or sides, it's usually way out of the area in which you'd want to have something sharp anyway.

With long and normal lenses, it's unlikely anything in the corners is at the same distance and in focus anyway.

No matter how sharp a lens, as soon as you move the smallest amount away from the plane of best focus, it gets softer. No mater how sharp someone's eye may be, their ears and tip of their nose will be in poorer focus than the eyes. These will be as out-of-focus regardless of the lens you use.

How to Use Your Lens Properly top

Know your gear's limitations, and work within them. This is the basis of everything people do.

For most lenses, this means stop down two stops from maximum to eliminate any residual aberrations and vignetting, and don't use the last two smaller apertures due to diffraction.

Some people freak out when a lens won't do something for which it was never intended. Some people will think that they have a defective sample of lens, where in fact all they're doing is looking too hard and finding that lens' limits.

The only lenses designed for shooting flat test charts are macro (and Nikon's micro) lenses. Every other photographic lens is designed for taking pictures of living, moving three-dimensional objects. Waste too much time worrying about corner sharpness and you'll die young.

Normal and telephoto lenses rarely have limitations, but even in 2008 zooms and ultra-wides still can be soft if you look too closely in the corners at too high a magnification.

It's normal for ultra-wide zooms to be horribly soft in the corners shot wide-open. The only ultra-wide zoom anyone's ever tested that is sharp in the corners at f/2.8 at the widest end is Nikon's 14-24mm f/2.8 AF-S. So what, when you shoot a wide lens wide-open, it's because it's dark, and the corners of your composition are probably unlit anyway.

Know your lenses' limitations and work around them. The real difference in sharpness between lenses is the range of conditions over which a lens works well. Know the conditions over which your system works well, and use it there for great results.

You know how important focus is to getting sharp pictures. Some camera and lens combinations, like the Nikon D300 and 60mm AF-S micro, get hung up and refuse to focus in some conditions. Yes, the 60mm is super-sharp for shooting test charts, but could be awful if it didn't focus and you missed your shot.

This is the reason real photographers may pay more for expensive gear. It's not because it works any better, in fact often cheap lenses are sharper under ideal conditions than more expensive lenses. Photographers pay more for some gear because it allows them to get great results over a broader range of conditions, not because it works any better in a lab under ideal conditions.

Use the Right Tools top

Within any format (35mm, DSLR, 120, 4x5, etc.), the sharpness of any image is limited mostly by the format. No matter how sharp your 35mm Leica might be, even a crummy medium format camera is much sharper.

This was never more apparent to me than when I got my first 4x5" camera in 1991. Holy guacamole, the results from the beat-up, scratched crummy lens I got on my Graflex was a zillion times sharper than any of my classic "sharpest lens ever made" manual-focus Nikkors like the 55mm f/2.8, 105mm f/2.8 AI-s Micro at the top of this page or 180mm f/2.8 ED.

If sharpness is your concern, be sure you're shooting the biggest format you can bear. If you shoot digital, shoot Canon full-frame or Nikon FX, if not medium format like the Mamiya ZD, or pop a Phase One P45 on your 4x5 camera. Don't expect that new lenses are going to make any difference with the same camera you've been using.

I kid you not: we in media were amused when the EXIF data of Nikon's press images of the D3 told us that they were shot on a P45 back. (These are the product shots you've seen everywhere in publicity and reviews of the D3). Nikon's not stupid, so why should you be? Nikon had a photographer who used the proper tools for a studio shot, not a news, sports and action camera like the D3.

All because common cameras like Nikon and Canon have huge marketing budgets doesn't mean you should be using them if you're shooting landscapes on a tripod. Getting a larger format camera is the way to go, and you can do it for under $2,000.

How to Check Sharpness top

The only lenses for which it makes sense to shoot charts are macro lenses. Most lenses are used at larger distances. Shooting a chart a few feet (meters) away has nothing to do with its sharpness at longer distances.

Even the slightest misalignment in most people's test setups causes more loss of sharpness than the lenses they are trying to test. Planes of best focus are very, very thin — much thinner than any depth-of-field.

For photographic purposes, you have to climb a mountain and shoot down. You have to do this when the seeing conditions are clear, and for longer lenses, when heat shimmer isn't happening, typically in the early morning, dusk, and at night.

By shooting from a mountain, all of the subject is at infinity over all of the frame, and there are tons of fine fractal detail everywhere, like vegetation. Your subject's alignment doesn't matter, since everything is at infinity all over the frame. Few people have access to mountains on clear days, which is why so many tests aren't done correctly and create apparent problems which don't exist.

Ansel Adams suggested using lines of trees along a distant mountain ridge as a target. I can't do that here in Southern California because all we have are rocks on the tops of our mountains. Ansel knew about fractals before Mandelbrot ever wrote about them. Fractals means that there are similar levels of detail at every magnification, so that regardless of how close or how far you are away from trees, complete forests or individual leaves, there is always detail to be seen. Buildings, newspaper classifieds, cars and signs don't have this quality: they have only sharp edges, but no textures, and if they have texture, it's at about only one level of detail.

Appropriate natural objects have detail at every magnification, and detail in every direction.

Focus needs to be perfect. Even the slightest error in your AF system or manual focus will cause unsharpness. With longer lenses, you have to choose your mountain carefully since objects closer than a mile start becoming a significant amount closer than infinity.

What Really Matters top

Just go take pictures. I know how to make lenses look awful in order to find their limits when testing them, but they always look a zillion times better when actually taken out and used to make real pictures. Only idiots shoot wide-open in daylight. (Fashion photographers shoot long teles wide-open, which look great.)

What really matters is how the lens feels in your hands. How well does it focus? Is there too much distortion for you? Does it zoom well, or does the zoom ring bunch some focal lengths too close together? Do you have to move switches to get into manual focus mode? (Some Nikon lenses take two switches!) Does the autofocus grab accurate focus, and if it does, does it do it every time? (Some Canon cameras and lenses completely "miss" a significant percentage of the time.)

Does VR or IS work well? Does the VR or IS system make too much chatter or hissing noise? Does the lens have VR or IS, without which it will be much less sharp in real shots at longer focal lengths?

Is the lens too big or heavy? Are the controls in comfortable positions? Is the focus ring in a place likely to get knocked by accident, as it is on the Nikon 24-70mm AFS?

Will your filters fit, and will they cause any vignetting? Are there ghosts if pointed into the sun?

Is it built to last, or will it fall apart?

Will the lens and all its features work on your camera?

Sharpness is the least of our worries.

Why Some People Worry About Sharpness top

News and media has always played on people's fears to get more readers and viewers. When I was a budding photographer and tried to sell car crash photos to the local paper, the first thing they asked me was if anyone died. If not, they didn't care. As we say in TV news, "if it bleeds, it leads."

Some men (never women) worry themselves silly about lens sharpness. When I started serious photography in the 1970s, I was warned that there is a segment of the hobby where all people do is take pictures of brick walls and newspaper classifieds, but never make any photos of anything worthwhile.

The people who worry the most are those with the least experience. Don't let this happen to you. Check each piece of new gear as it arrives, but then get out and shoot.

And Again, Who Cares? top

All this has been presuming you want a sharp photo. Being sharp has little to do with being a good photo, unless you're doing forensic work. Many great photos use deliberate unsharpness to express their points, and if you look at sales and auction prices of photos as art you'll see that the fuzzier ones sell for much more.

Sharp photos are boring. Photos that are sharp all over are usually amateur attempts, which glaringly show too much detail for many unrelated, confusing and distracting elements. A good photo has impact and a punch line. The fewer things a photo tries to say, the more powerfully it says them. Things need to stand out. Having everything sharp edge-to-edge rarely makes for a strong photo.

Have a look at PDN's May 2008 Photo Annual, where there are at least 400 hand-picked examples of the best professional photography from every category from advertising to journalism to sports to stock. Look in the corners, and every single shot has fuzzy corners, or more likely, deliberately darkened, white or otherwise detail-free corners.

You don't put details in your corners. It distracts the viewer and weakens your image.

Some people think I'm a decent photographer. Do you know what limits the sharpness of most of my photos, even those made with crappy equipment? It's the same things I mention elsewhere: imperfect focus, limited depth-of-field, and subject and camera motion.

Your creative input to a photo makes far more of an imprint on the image than any small, and often invisible, difference in sharpness from one lens to another.

Sharpness. Just get over it.

Help me help you top

I support my growing family through this website, as crazy as it might seem.

The biggest help is when you use any of these links when you get anything, regardless of the country in which you live. It costs you nothing, and is this site's, and thus my family's, biggest source of support. These places have the best prices and service, which is why I've used them since before this website existed. I recommend them all personally.

If you find this page as helpful as a book you might have had to buy or a workshop you may have had to take, feel free to help me continue helping everyone.

If you've gotten your gear through one of my links or helped otherwise, you're family. It's great people like you who allow me to keep adding to this site full-time. Thanks!

If you haven't helped yet, please do, and consider helping me with a gift of $5.00.

As this page is copyrighted and formally registered, it is unlawful to make copies, especially in the form of printouts for personal use. If you wish to make a printout for personal use, you are granted one-time permission only if you PayPal me $5.00 per printout or part thereof. Thank you!

Thanks for reading!

Mr. & Mrs. Ken Rockwell, Ryan and Katie.

Home Donate New Search Gallery Reviews How-To Books Links Workshops About Contact